NeuroSnake: When TinyML Meets Classic Gaming in a Snake-Shaped PCB

The Wrong Approach Is

What happens when you combine a beloved retro game, cutting-edge machine learning, and the creative spirit of DEFCON badge culture? You get a snake-shaped PCB that learns to play Snake by itself, powered by neural networks running on a microcontroller with just 256KB of RAM.

The entire project was carried out by the following team: Mikołaj Markiel, Karol Szczepanik, Dzmitry Astrouski, Bart Szczepański.

From electronic art to semi-autonomous intelligence

The world of conference badges has evolved into something remarkable, from simple blinking LEDs to sophisticated interactive electronics that push the boundaries of portable computing. These pocket-sized marvels represent a unique intersection of art, engineering, and hacker creativity.

Looking at these designs - skull-shaped PCBs with mesmerizing LED arrays, intricate circuit-pattern artwork, and collections spanning years of innovation. It's clear they represent more than decorative electronics. They embody a culture where extreme constraints spark the most creative solutions.

The challenge is always the same: how do you pack maximum functionality into a tiny, battery-powered device that's actually worth wearing? Solutions have ranged from mesh networking to puzzle games, from cryptocurrency miners to full computers.

But seeing this evolution sparked a different question: What if a badge didn't just react to input, but could learn and adapt? What if we could fit genuine machine learning into something small enough to pin to your shirt?

The answer lay in TinyML, a revolutionary approach that's bringing machine learning to the smallest devices imaginable.

Intelligence at the Edge of Everything

TinyML marks a radical shift in artificial intelligence. While traditional AI relies on massive cloud servers and models with billions of parameters, TinyML brings intelligence directly to devices running on just kilobytes of memory and milliwatts of power.

Instead of sending sensor data to the cloud, devices make smart decisions locally, enabling:

- Privacy by Design: Your data never leaves your device,

- Ultra-Low Latency: No network round trips, instant responses,

- Energy Efficiency: Optimized for battery-powered operation,

- Always Available: Works without internet connectivity.

For badges and wearable electronics, TinyML opens up possibilities that were unimaginable just a few years ago. Imagine a badge that recognises your gestures, learns your preferences, or plays games autonomously, all while running for days on a single battery charge.

NeuroSnake became our exploration of this frontier, taking the universally understood game of Snake and asking, “Can we teach a neural network to master it using only the resources available on a badge-sized device”?

The Evolution of Game Intelligence

The transition from simple reinforcement learning to neural network-based agents represents an important milestone in the field of artificial intelligence. To see why NeuroSnake needed deep learning, it helps to understand where traditional methods fall short.

Classic Q-learning builds a table of state–action values, perfect for small, discrete environments. But Snake, even in its apparent simplicity, presents a combinatorial explosion of possible game states. With a 32x24 grid, a snake that can be any length, and food that can appear anywhere, the number of unique states quickly becomes astronomically large.

Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) solve this by replacing the table with a neural network that learns to recognise patterns and predict action values. This enables the agent to handle entirely new situations.

The real innovation came in state representation: instead of raw pixels, we designed an 11-dimensional state vector capturing the game’s core dynamics:

1def _get_state(self):

2 """Get current state for the Q-learning agent"""

3 head = self.snake_body[0]

4

5 # Calculate adjacent points for collision detection

6 point_l = (head[0] - self.block_size, head[1])

7 point_r = (head[0] + self.block_size, head[1])

8 point_u = (head[0], head[1] - self.block_size)

9 point_d = (head[0], head[1] + self.block_size)

10

11 # Current direction (one-hot encoded)

12 dir_l = self.direction == 'LEFT'

13 dir_r = self.direction == 'RIGHT'

14 dir_u = self.direction == 'UP'

15 dir_d = self.direction == 'DOWN'

16

17 # Collision detection relative to current direction

18 danger_straight = (

19 (dir_r and self._is_collision(point_r)) or

20 (dir_l and self._is_collision(point_l)) or

21 (dir_u and self._is_collision(point_u)) or

22 (dir_d and self._is_collision(point_d))

23 )

24

25 danger_right = (

26 (dir_u and self._is_collision(point_r)) or

27 (dir_d and self._is_collision(point_l)) or

28 (dir_l and self._is_collision(point_u)) or

29 (dir_r and self._is_collision(point_d))

30 )

31

32 danger_left = (

33 (dir_d and self._is_collision(point_r)) or

34 (dir_u and self._is_collision(point_l)) or

35 (dir_r and self._is_collision(point_u)) or

36 (dir_l and self._is_collision(point_d))

37 )

38

39 # Food location relative to head

40 food_left = self.food[0] < head[0]

41 food_right = self.food[0] > head[0]

42 food_up = self.food[1] < head[1]

43 food_down = self.food[1] > head[1]

44

45 return np.array([

46 danger_straight, danger_right, danger_left,

47 dir_l, dir_r, dir_u, dir_d,

48 food_left, food_right, food_up, food_down

49 ], dtype=int) This compact representation creates an 11-dimensional state vector:

- 3 collision danger flags (straight, right, left),

- 4 direction flags (left, right, up, down),

- 4 food direction flags (left, right, up, down).

The neural network learns to map this 11-dimensional input to optimal actions, developing strategies that go far beyond simple rule-based behavior.

The neural network architecture is designed specifically for this 11-dimensional input:

1def _build_model(self):

2 """Neural Network for Deep Q-Learning"""

3 model = tf.keras.Sequential([

4 # 11-dimensional state input

5 tf.keras.Input(shape=(11,)),

6 # Hidden layer 1

7 tf.keras.layers.Dense(24, activation='relu'),

8 # Hidden layer 2

9 tf.keras.layers.Dense(24, activation='relu'),

10 # 3 actions output (straight, right, left)

11 tf.keras.layers.Dense(3, activation='linear')

12 ])

13 model.compile(loss='mse',

14 optimizer=tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.001))

15 return modelThis compact yet powerful architecture takes the 11-dimensional state vector and outputs Q-values for three possible actions: go straight, turn right, or turn left.

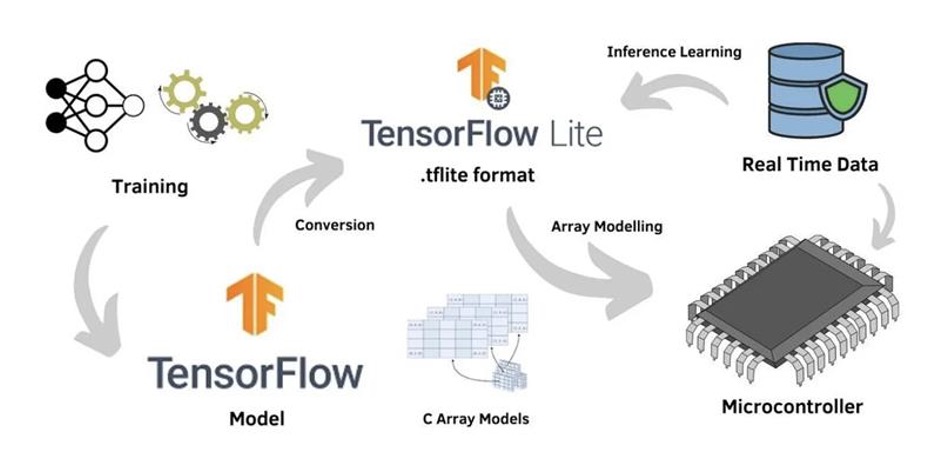

The magic happens in the model conversion pipeline, where our trained neural network gets transformed for embedded deployment through TensorFlow Lite, now rebranded as [LiteRT](https://developers.googleblog.com/en/tensorflow-lite-is-now-litert/) to better reflect its runtime focus:

This pipeline represents the bridge between cloud-scale AI development and edge deployment, taking our full-precision neural network and optimizing it for the severe constraints of microcontroller hardware.

Python and Simulation: Building the Training Ground

Before deploying intelligence to a microcontroller, we first had to build a space for it to learn and evolve and Python with Pygame gave us the perfect playground for rapid experimentation.

The training environment needed to be fast enough for thousands of episodes while accurately representing the embedded game mechanics:

1class SnakeGame:

2 def __init__(self, width=640, height=480, speed=40):

3 self.width = width

4 self.height = height

5 self.block_size = 20

6

7 # Initialize Pygame environment for training

8 pygame.init()

9 self.display = pygame.display.set_mode((width, height))

10 self.reset()

11

12 def step(self, action):

13 """Perform one step: 0=straight, 1=right turn, 2=left turn"""

14 self.steps += 1

15

16 # Apply action to change direction

17 self._update_direction(action)

18

19 # Move snake head

20 new_head = self._calculate_new_head()

21 self.snake_body.insert(0, new_head)

22

23 # Check for collision or food

24 reward = 0

25 game_over = False

26

27 if self._is_collision(new_head) or self.steps > 100*len(self.snake_body):

28 game_over = True

29 reward = -10 # Collision penalty

30 elif new_head == self.food:

31 self.score += 1

32 reward = 10 # Food reward

33 self.food = self._place_food()

34 else:

35 self.snake_body.pop() # Remove tail

36

37 return self._get_state(), reward, game_over

The reward system was key. At first, sparse rewards (+10 for food, -10 for collisions) made agents spin in circles. Adding a small step penalty encouraged food-seeking behavior while preventing infinite loops.

The neural network architecture needed to be sophisticated enough to learn complex strategies while remaining deployable on a microcontroller:

1def _build_model(self):

2 """Neural Network for Deep Q-Learning"""

3 model = tf.keras.Sequential([

4 tf.keras.Input(shape=(11,)), # 11-dimensional state

5 tf.keras.layers.Dense(24, activation='relu'), # Hidden layer 1

6 tf.keras.layers.Dense(24, activation='relu'), # Hidden layer 2

7 tf.keras.layers.Dense(3, activation='linear') # 3 actions output

8 ])

9

10 model.compile(

11 loss='mse',

12 optimizer=tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate=0.001)

13 )

14 return model Two hidden layers of 24 neurons gave the model enough power for smart behavior without overfitting. The output layer calculates Q-values for three actions: forward, right, or left. After thousands of episodes, the agent learned advanced tactics like wall-following, spiral searching, and avoiding collisions before they happened.

Nordic nRF54L15 and TinyML Capabilities

Selecting the hardware platform was critical. Neural inference demanded strong performance, while badge constraints required low power use and minimal memory. The Nordic nRF54L15, a microcontroller designed specifically for the TinyML era, was selected.

With an Arm Cortex-M33 at 128 MHz, 256 KB of RAM, and 1.5 MB of Flash, the nRF54L15 delivers a strong balance for embedded AI. Its power management keeps inference running efficiently - essential for a continuously thinking badge.

Beyond compute capability, TinyML depends on the right architecture:

- Efficient Multiply-Accumulate (MAC) Operations: essential for neural network matrix multiplications,

- Low-Power Sleep Modes: to conserve battery during idle periods,

- Fast Memory Access: minimizing latency during inference,

- Adequate RAM: for tensor operations and intermediate calculations.

1// TensorFlow Lite Micro configuration

2static const int kInputSize = 11; // 11-dimensional state vector

3static const int kOutputSize = 3; // 3 actions: straight, right, left

4

5static constexpr int kTensorArenaSize = 4 * 1024; // 4KB memory arena

6static uint8_t tensor_arena[kTensorArenaSize];

7

8static tflite::MicroInterpreter* interpreter = nullptr;

9static TfLiteTensor* input_tensor = nullptr;

10static TfLiteTensor* output_tensor = nullptr; The memory was a major constraint. Unlike desktop AI with gigabytes available, embedded systems must pre-allocate every byte. The 4 KB tensor arena reflects a precise balance between model capability and system stability.

The TensorFlow Lite Micro initialisation sets up the inference engine:

1// Create a MicroMutableOpResolver for the required operations

2static tflite::MicroMutableOpResolver<4> micro_op_resolver;

3micro_op_resolver.AddFullyConnected();

4micro_op_resolver.AddMul();

5micro_op_resolver.AddAdd();

6micro_op_resolver.AddRelu();

7

8// Create the interpreter with the pre-allocated memory arena

9static tflite::MicroInterpreter static_interpreter(

10 model, // The embedded model data

11 micro_op_resolver, // Operation resolver

12 tensor_arena, // Pre-allocated memory

13 kTensorArenaSize // Arena size (4KB)

14);

15interpreter = &static_interpreter;

16

17// Allocate memory from the tensor arena

18if (interpreter->AllocateTensors() != kTfLiteOk) {

19 printk("AllocateTensors() failed");

20 return;

21}

22

23// Get input and output tensor references

24input_tensor = interpreter->input(0);

25output_tensor = interpreter->output(0); This initialisation demonstrates the importance of careful memory management in TinyML. Every byte is accounted for, and all allocations are made at start-up to avoid fragmentation.

Consuming the Trained Model

The shift from Python training to C++ inference is a crucial step in TinyML. The trained network must be converted and tightly optimized to fit the strict limits of microcontroller hardware.

The conversion pipeline transforms the Keras model into an embedded-friendly format:

1def convert_to_tflite(model_path='dqn_model.keras', tflite_path='model.tflite'):

2 # Load the trained Keras model

3 model = tf.keras.models.load_model(model_path)

4 converter = tf.lite.TFLiteConverter.from_keras_model(model)

5 tflite_model = converter.convert()

6

7 # Save the TFLite model

8 with open(tflite_path, 'wb') as f:

9 f.write(tflite_model)

10

11 # Generate C header with model weights

12 with open('model_data.h', 'w') as f:

13 f.write("const unsigned char model_data[] = {")

14 f.write(",".join([hex(x) for x in tflite_model]))

15 f.write("};\n")

16 f.write(f"const unsigned int model_data_len = {len(tflite_model)};\n")

17

18 print(f"Model converted and saved to {tflite_path}")

19 print("C header file generated as model_data.h") This pipeline converts a Keras model with floating-point precision to TensorFlow Lite format and generates a C header file containing the model as a byte array that can be compiled directly into firmware.

The C++ inference code consumes this converted model to make real-time decisions:

1static int getActionFromModel(void) {

2 // Fill input tensor with 11-dimensional state vector

3 float* input_data = input_tensor->data.f;

4 for (int i = 0; i < kInputSize; i++) {

5 input_data[i] = 0.0f;

6 }

7

8 // Set direction bits (one-hot encoding)

9 switch (snake_dir) {

10 case DIR_UP: input_data[5] = 1.0f; break;

11 case DIR_RIGHT: input_data[4] = 1.0f; break;

12 case DIR_DOWN: input_data[6] = 1.0f; break;

13 case DIR_LEFT: input_data[3] = 1.0f; break;

14 }

15

16 // Set food direction bits

17 int head_x = snake[0].x;

18 int head_y = snake[0].y;

19 if (food_x < head_x) input_data[7] = 1.0f; // food_left

20 if (food_x > head_x) input_data[8] = 1.0f; // food_right

21 if (food_y < head_y) input_data[9] = 1.0f; // food_up

22 if (food_y > head_y) input_data[10] = 1.0f; // food_down

23

24 // Run neural network inference

25 if (interpreter->Invoke() != kTfLiteOk) {

26 return 0; // Default action on inference failure

27 }

28

29 // Extract best action using argmax

30 float* output_data = output_tensor->data.f;

31 int best_idx = 0;

32 float best_val = output_data[0];

33 for (int i = 1; i < kOutputSize; i++) {

34 if (output_data[i] > best_val) {

35 best_val = output_data[i];

36 best_idx = i;

37 }

38 }

39 return best_idx; // 0=straight, 1=turn right, 2=turn left

40} This code presents the full pipeline: creating the same 11-dimensional state vector as in Python training, running neural network inference, and selecting the action via argmax. The embedded version matches the Python logic while fitting within a 4KB memory limit. Quantization cuts the model size by ~75% while preserving solid gameplay performance.

Creative Engineering Meets Art

The physical design shows how circuit boards can become works of art while maintaining full functionality.

.png)

The PCB artwork shows how circuit boards can go beyond pure function. Its snake-shaped layout embeds every component into a fluid, organic form that makes the technology feel alive and inviting. The sophisticated layout of the printed circuit board demonstrates attention to both aesthetics and functionality, with the placement of components following the natural curves of the snake pattern while maintaining proper electrical connections.

Bringing It All Together

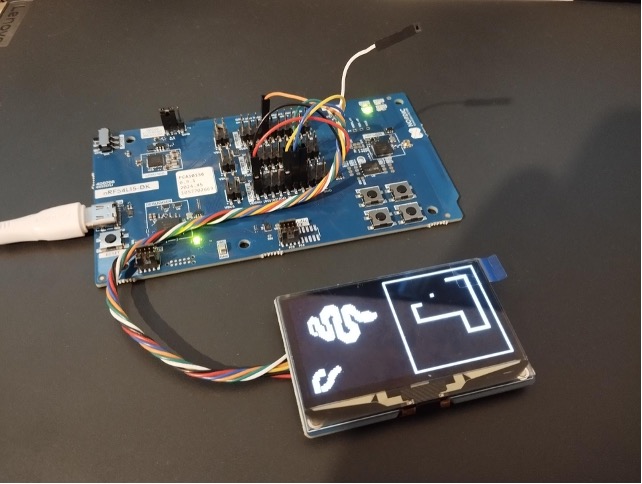

The development process culminated in a working demonstration of TinyML running on badge-sized hardware, showing how complex AI concepts can be made tangible and approachable.

The snake-shaped PCB and OLED display deliver a unique, eye-catching form factor that makes advanced AI concepts tangible and approachable. This badge highlights key TinyML capabilities: efficient neural network inference, power-optimized acceleration, and continuous battery-powered operation.

Watching the badge in action highlights a core truth of TinyML: meaningful intelligence doesn’t require heavy computing power. With smart optimization, even a badge-sized device can deliver machine intelligence approaching human performance. Its power efficiency is especially notable, averaging just 45 mA during gameplay, it can run for over 8 hours, proving that AI and battery life can coexist effectively.

Our Final Perspective

This project reveals something exciting about TinyML: true intelligence doesn’t need the cloud or heavyweight hardware. With smart optimization and thoughtful design, even palm-sized devices can make sophisticated decisions on their own, improving privacy, reducing latency, and putting AI directly into people’s hands.

Snake may be a simple game, but when it learns to outsmart you on a microcontroller, it shows a much bigger shift: The future of artificial intelligence is not only about greater power, but also greater efficiency.

Rapidly adapt our competences into your IoT solution

Contact us and share your challenges